12 Principles of Animation

Applied to 3D Animation

In the early 1930s, Walt Disney and company sat down to codify the hand-drawn animation process that had been informally evolving at Walt Disney studios. What emerged became known as the “12 Principles of Animation,” and set the standard for hand-drawn animation.

At Saturday morning’s “The 12 Principles of Animation applied to 3D Animation,” Isaac Kerlow, Director of Digital Production at the Walt Disney Company, argued that the principles need to be adapted for the modern day. Using visual examples from well-known animated films, Kerlow reinterpreted the twelve principles as they would apply to 3D animation, and added a few new ones of his own.

The purpose of adapting the principles, Kerlow said, is to guide the development of 3D animation, a relatively new art form. Computer animation is very complex, and a well-understood framework can help artists and producers weave together the many separate aspects of character and scene creation, into an animated tapestry that will truly captivate an audience.

For each of the following twelve principles, Kerlow defined the intention of the principle, presented a visual example to back it up, and suggested a modern equivalent that would apply to character artists working in 3D.

1. Squash and Stretch

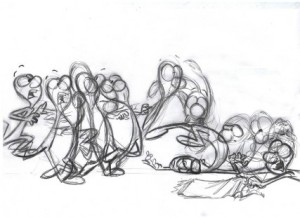

Original idea: In traditional animation, characters movements (particularly facial movements) had a very high degree of exaggerated, non-rigid deformation. (Imagine any Disney character whose face contorts wildly during a sneeze or a scream.)

Modern equivalent: The principle still holds in the 3D era, especially for cartoon-like animations. (Anime tends toward exaggerated subtlety.) Squashing and stretching happen within animation packages, using dynamics weighting or unusual IK systems.

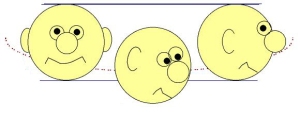

2. Anticipation

Original idea: Anticipation is the technique by which the audience’s eyes are drawn to where action will occur on-screen (e.g. a cartoon that begins making running motions before actually going anywhere). Anticipation announces the coming surprise and is a very useful technique for guiding expectation. (Again, Disney animation tends toward heavy anticipation, whereas in anime we see very little — given anime a more etheric, fantastic feel.)

Modern equivalent: Anticipation can be created by the skillful use of motion curves, expanding or contracting pieces of animation to create the anticipatory effect.

3. Staging

Original idea: Staging refers to the way in which character motion and camera movements are set up to convey the mood and intent of a scene. (Example: in Toy Story, Buzz Light year’s arrival in the bedroom is shown with a close-up that begins at his feet and pans dramatically upward to his helmet.)

Modern equivalent: In 3D, staging can be expanded to include more detail, hide points of interest, set up for chain reactions, and so on. Staging is also useful in animistic, which establish a scene’s core movements before primary animation gets underway. Contemporary moving image techniques, such as 3-axis camera moves, slow motion, “bullet time,” and so on, also add to 3D staging abilities.

4. Straight Ahead or Pose-to-Pose

Original idea: In traditional animation, character actions were either drawn from beginning to end, creating an unpredictable look and feel, or they were broken down into a more predictable set of key poses.

Modern equivalent: In 3D animation, straight ahead animation corresponds to procedural animation techniques (e.g. motion capture and 3D rotoscoping); pose-to-pose would correspond to key frame animation. Modern artists can take advantage of layers or channels to intelligently mix both types of motion, or use non-linear motion curve editing to edit different aspects of a single character’s motion.

5. Follow-Through and Overlapping

Original idea: Follow-through refers to the reactive animation that occurs after an action is completed, telling the audience how the character feels about that action. (Think of Donald Duck throwing a football, watching it for a moment, and then lowering his arm in disappointment.) Overlapping refers to the additional motions that overlap the main motion of a given character.

Modern equivalent: Follow-through can be done with dynamic simulation and scripts – especially for cloth and hair. Overlapping is achieved by using layers and channels to blend different types of motion into a sequence.

6. Slow-in and Slow-out

Original idea: If you look closely at movies animated in the Disney style, you’ll see that characters’ motions tend to be quicker in the middle of an action than at the beginning and end. This slowing of the intro and extra sections of a movement creates a “snappy” effect.

Modern equivalent: Fine-tuning animations using time-editing tools, such as dope sheets, curves, and timelines. Motion capture performers can also be directed to do slow-ins and slow-outs.

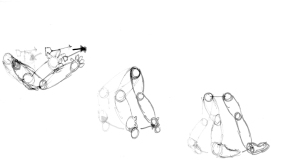

7. Arcs

Original idea: Organic characters almost always move in motion arcs, as opposed to straight lines. Straight line motions make a character look sinister, robotic, or restricted in some way. (In The Iron Giant, the giant begins the movie with linear movements, and adopts arc-based motion as he becomes “more human” later on.)

Modern equivalent: In 3D packages, motion can easily be constrained to arcs. Motion capture performances can also be fine-tuned using arc editors.

8. Secondary Action

Original idea: These are small complementary motions that occur in a scene.

Modern equivalent: Using layers and channels to build up different aspects of secondary motion. Collision detection is another useful tool for generating secondary actions.

9. Timing

Original idea: Timing refers to the precise moment at which a given character motion occurs, and how long it continues for. (Humor is often created through the use of clever timing juxtapositions.)

Modern equivalent: In 3D animation, timing can be refined using the time-editing tools, and frames can be easily added or removed to make the timing work. Using different animation tracks for different character (and sub-tracks for parts of characters) also helps create precise timing.

10. Exaggeration

Original idea: The essence of an action is often enhanced by the exaggeration of a given motion – especially for cartoon-style animation. (Eyes bugging out, jaws dropping, etc.)Modern equivalent: In 3D, this can be done at the performance level, using procedural techniques, and can also be worked into cinematography and editing.

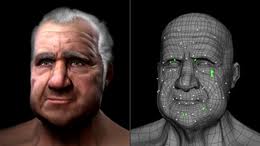

11. Solid Drawing

Original idea: Originally, this principle referred to using appropriate weight, depth and balance to give drawings the desired look.

Modern equivalent: Kerlow suggested renaming this principle “Solid Modeling and Rigging,” since the same principles now apply to the optimization of models and IK skeletons to create specific “animation personalities” for different characters.

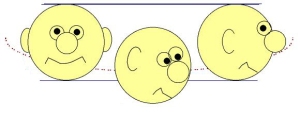

12. Characters’ Appeal

Original idea: The last of the twelve principles suggests that characters be well-developed, with interesting and distinct personalities.

Modern equivalent: In 3D animation, character complexity and consistency can be dramatically increased – and built in to a character’s design – so that appeal is not being recreated from scratch with every set of drawings. Kerlow pointed out that in gaming, walk and run cycles are especially important aspects of a character’s appeal. He showed a clip from Kingdom Hearts in which Sora, Donald, and Goofy are walking side by side, each with their own distinct style.

The use of color is an important aspect of character design.It must be in keeping with the general design concept and fit comfortably with the rest of the design elements of the production. A multitude of psychedelic colors outlined by a heavy black line may not be what is required if the backgrounds are to be painted in delicate Chinese watercolor techniques. Color must also be used with care when targeting a specific audience. Designs using bright primary colors may be appropriate for a pre-school TV series but unsuitable for a darker piece aimed at an adult audience.

The use of color is an important aspect of character design.It must be in keeping with the general design concept and fit comfortably with the rest of the design elements of the production. A multitude of psychedelic colors outlined by a heavy black line may not be what is required if the backgrounds are to be painted in delicate Chinese watercolor techniques. Color must also be used with care when targeting a specific audience. Designs using bright primary colors may be appropriate for a pre-school TV series but unsuitable for a darker piece aimed at an adult audience.